Current art-historical debates increasingly emphasize the role of visual rhetoric, used by actors to engage in “kolportage”, the repeated dissemination of strongly simplified image and text patterns, to discredit climate protection efforts or safeguard existing economic interests.

Such campaigns employ visual strategies that evoke the effects of historical propaganda forms and deliberately steer emotions.

A central method is the aesthetics of iconoclasm.

Images of alternative energy projects (such as wind turbines in cultural landscapes) are coupled with negatively connoted associations (storms, scrap, utopian cultists). This technique can be comparatively studied through the Liberate Tate actions, which, in reverse, expose the sponsorship relationship between fossil fuel corporations and art institutions, rather than obscuring it.

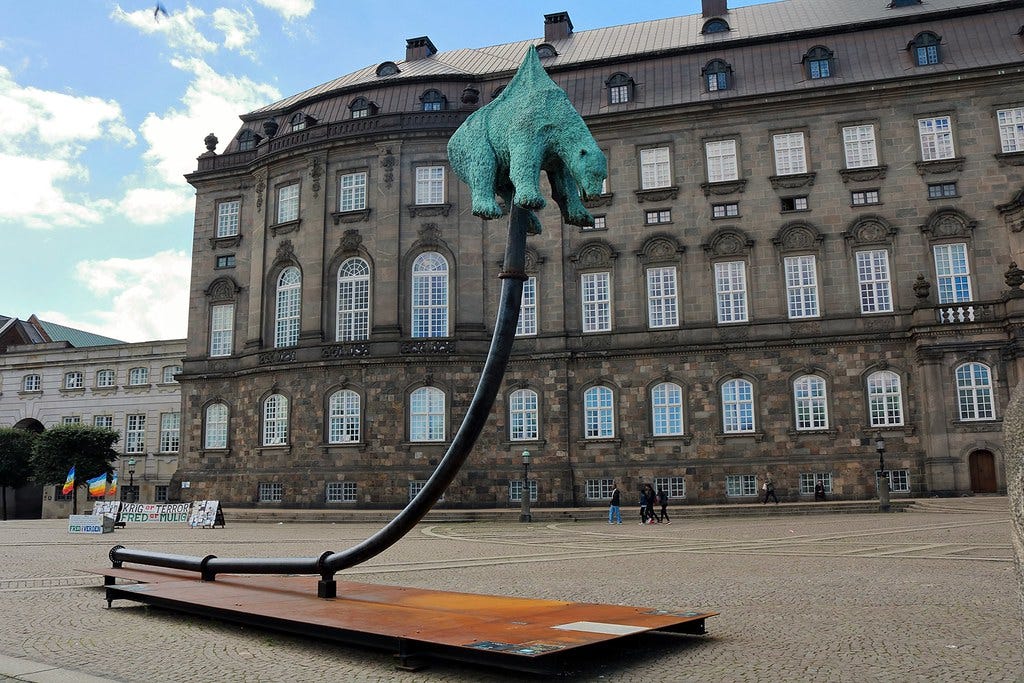

Similarly, Jens Galschiøt’s Unbearable sculpture employs the impaling motif.

Through the image of a polar bear impaled on an oil pipeline diagram, it appeals to empathy and outrage, while counter-images in kolportage stylize the animal as a "natural predator" unworthy of sympathy.

Collectives like Cape Farewell (2001) engage in transmedial expeditions to intertwine science and the arts. Their strongly narrative storytelling strategies leverage the emotional resonance of scientific facts in artistic formats to establish counter-publics against climate-hostile kolportage.

Contemporary street art uses participatory aesthetics, such as the wall paintings by BOHIE, to explore themes of hope and responsibility, offering a counter-model to emotionally charged panic imagery.

In the sphere of political visual culture, such interventions compete with deliberately seeded fake visuals (manipulated photos that exaggerate climate disasters or include fabricated “expert statements”). Research projects using AI-assisted image recognition (University of Potsdam) decode these rhetorical patterns and reveal how frequently representatives of political status-quo interests employ the same visual stereotypes.

In conclusion, art–science collaborations (Max Planck Institute, Humboldt University Berlin) demonstrate the necessity not only to analyze visual strategies but to actively create counter-narratives.

Interdisciplinary funding programs such as Horizon Europe or DFG initiatives make it possible to position art as a political instrument against disinformation-based kolportage and to design visionary spaces for the future.

KB

Sources

Reid, M. “I used to conserve artworks. Now I’m in prison for climate action.” The Guardian, Oct. 2024. theguardian.com

Motion, J. “Undoing art and oil…” Environmental Politics 28(4), 2019. tandfonline.com

GC – Climate Stories. Geo-Climatic Perspectives 5, 2022. gc.copernicus.org

Artsper Magazine. “Radical Artworks on Climate Change.” 2024. blog.artsper.com

Cape Farewell. Wikipedia (EN), en.wikipedia.org

Jens Galschiøt, Unbearable (2015). Wikipedia (EN). en.wikipedia.org

BOHIE et al. “Street art as a vehicle for environmental science communication.” JCOM, 2023. jcom.sissa.it