George Nelson (1908–1986) and Peter Zumthor (b. 1943) are among the most influential figures of modernity, albeit in different contexts.

Although Nelson and Zumthor differ in discipline and vision, they share an ethically grounded stance, manifested in Nelson’s approach to functional living and in Zumthor’s to sensual experience.

Nelson shaped industrial design and modern lifestyle in the United States, particularly through his work for Herman Miller, while Zumthor redefined architecture as a sensory art form rooted in craftsmanship, materiality, and place. Nelson’s systemic thinking and sensitivity to everyday spaces meet in Zumthor an architecture of atmospheric expression. Both are bridge-builders.

Nelson spelled out the relationship between everyday use and visual environment. He studied at the Yale School of Art and later became editor-in-chief of Industrial Design magazine. As Design Director at Herman Miller (1947–1972), he worked with talents such as Charles and Ray Eames and Alexander Girard. His advocacy, conferences such as the Aspen Design Gatherings, and publications legitimized design as a societal force.

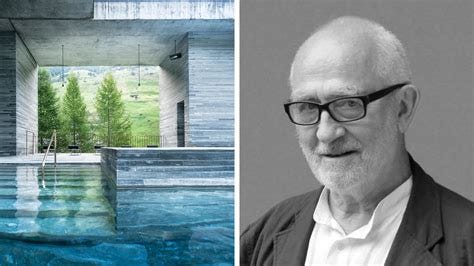

Zumthor draws between nature, material, and space. Raised in Switzerland, he trained as a cabinetmaker and later studied architecture. Teaching positions at Pratt Institute, USC, Harvard, and Mendrisio shaped his path. In 1979, he founded his own studio. His approach is characterized by craftsmanship, sensitivity to materials, and a sensory atmosphere.

They leave behind guiding principles for a future in which design assumes deep responsibility, for both practical living spaces and spiritual places.

In doing so, both articulate relevance beyond their time.

Nelson argued that design is a social responsibility, and many of his furniture designs promote quality of life and spatial efficiency. He developed modular living environments and usage structures (office cubes, mall concepts), seeing design as a societal mission.

He avoided visual pollution through design, advocating for more sustainable living environments. His work was socially driven, less aesthetically or artistically oriented. His functionalism, with orthogonal, organized forms for everyday contexts, was additive, not imposing.

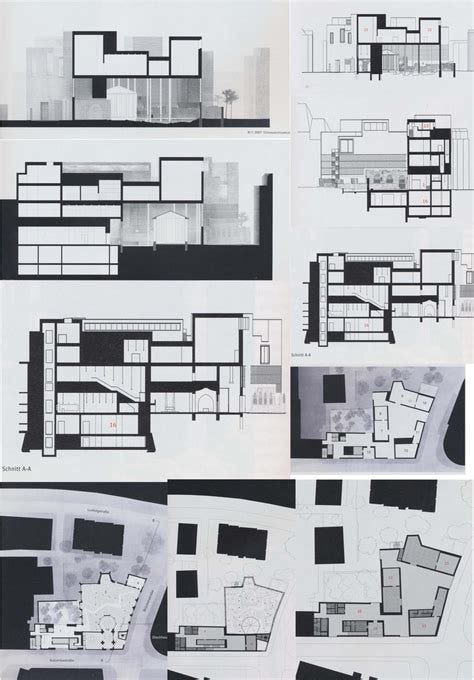

Zumthor, by contrast, strives for aesthetic and material integrity beyond fleeting trends, and promotes architecture deeply rooted in experience. He develops his buildings as total experiences. Space, light, material, and dialogue shape places into environments with strong identity. His architecture invites engagement with living space and sensitizes users to ecological interrelationships.

He makes nature tangible. Function aims at atmosphere; form is determined by feeling, materiality, and place. The Therme Vals integrates rock and water into a heightened sensory experience; the Serpentine Pavilion places visitors in dialogue with vegetation and light. His architecture becomes an art form in itself—sensual, minimalist, reflective, in harmony with nature.

Nelson was an active designer, publishing extensively about his ideas, and highly engaged in the functional design of everyday life. He developed prefabricated, sustainable housing and work forms—anticipating resource-conscious living environments.

Zumthor begins intuitively, often avoiding overt theory; he favors silence and sensuality and positions himself against concept-heavy approaches (e.g., Eisenman). He demonstrates how architecture can be sustainable through local materials, high-quality craftsmanship, and durable, site-specific concepts.

Together, they show how design and architecture can impact the environment, community, and culture.

KB

Sources

Peter Zumthor – Biography, Philosophy & Work – en.wikipedia.org

Beautiful Silence – ACSF – acsforum.org

George Nelson – Designer – en.wikipedia.org

On sensory architecture and nature – Rethinking The Future